Canoe slalom venue for the Paris 2024 Olympics under construction – from VAIRES, stade d’eau vive #JO2024 2017

Editor’s foreword

Experienced journalist and Redlands resident Peter Wear has written eloquently to a Senate inquiry, about the $100 million Olympic canoe slalom venue proposed for Birkdale.

Australia’s preparedness to host the Brisbane 2032 Olympics and the 2026 Commonwealth Games in Victoria are currently being considered by the Senate Committes for Rural and Regional Affairs, and Transport.

Mr Wear has kindly agreed to allow Redlands2030 to publish much of his submission, to assist the Redlands community in understanding why there is no need for Australia to develop a new canoe slalom venue.

Submissions to this Senate inquiry close on 29 May 2023. More information is available on the Senate’s Inquiry Home Page.

There is also an opportunity to have your say about a proposal by Redland City Council to adopt a planning mechanism known as a Local Government Infrastructure Designation (LGID) to facilitate development of a whitewater facility and much other development on the Birkdale site. Redlands2030 has prepared a short template for you to oppose adoption of the LGID – submissions close on Monday 22 May 2023.

Proposal for an Olympic Canoe Slalom venue to be built at Birkdale in Redland City – by Peter Wear

Background

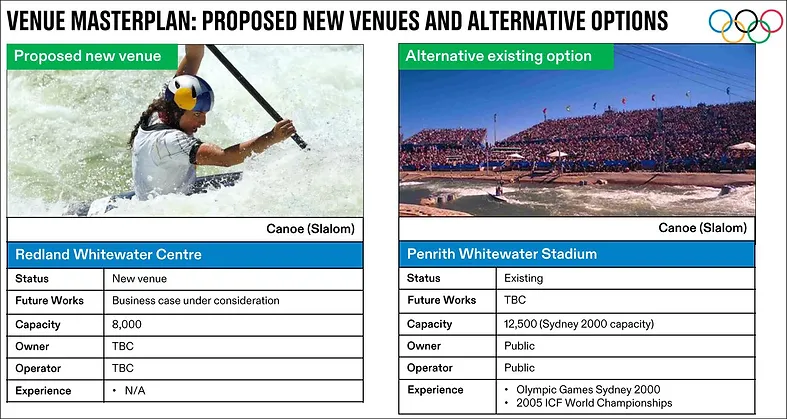

For nearly two years, the Redland City Council has been strenuously campaigning to host the canoe slalom events at the 2032 Brisbane Olympics. To this end, Council is proposing that a major whitewater course be built on acreage it owns in the suburb of Birkdale. The site currently appears on official Olympic communications as the canoe slalom venue for the Brisbane Games.

The cost of constructing an Olympic whitewater course can easily exceed $100 million dollars.¹ At the Paris Olympics next year 82 paddlers will line up for the canoe slalom.²

The Brisbane Games, on those figures, would have to commit over a million dollars per competitor to hosting a sport with fewer Olympic participants than handball, fencing, or skateboarding.

The International Olympic Committee has already moved decisively against such extravagance. The Brisbane Games is contractually bound to comply with the IOC’s direction that new Olympic infrastructure not be built if an existing facility is a practicable alternative. This contract will benchmark sustainability and cost constraint. In my view, the Birkdale proposal conspicuously fails both tests.

Moreover, an Olympic-standard venue already exists in New South Wales. The Penrith Whitewater Centre was built for the Sydney Games in 2000. As the IOC is well aware, the PWC is ready, willing and able to host the Olympic canoe slalom, again, in 2032.

The adequacy of existing sporting infrastructure to host Games events

Australia already has an Olympic-standard canoe slalom course – the Penrith Whitewater Centre, near Sydney. Built for the Games in 2000, it is still the sport’s premier venue in the southern hemisphere. Penrith will host the International Canoe Federation’s World Championships in 2025 – the ICF’s ultimate seal of approval.

The future of the Penrith Whitewater Centre has been secured by the NSW government taking it over from July this year, and announcing it will spend millions upgrading its infrastructure.³

In early 2021, the International Olympic Committee’s feasibility assessment⁴ of the Brisbane Games gave Penrith equal billing, as its sanctioned alternative, to the construction of a new whitewater course in Redland City.

The IOC has pledged the Games will be “climate positive” by 2024. The first principle of its Sustainability Strategy, that underpins the pledge, is ‘use of existing infrastructure is maximised.’ Games officials must put aside ‘location loyalty’, and consider existing venues, however distant from the host city.

Organisers of the Los Angeles 2028 Olympics, have been quick to get on message. California, like Queensland, has no Olympic whitewater course. They are finalising a ‘venue offset’ to transfer the LA Olympic canoe slalom interstate, nearly 2,000 kilometres east, to Oklahoma City’s Riversport complex.

What a mockery this would make of Brisbane 2032, four years later, spending $100 million on a whitewater course duplicating the one ‘down the road’ in Sydney.

The legacy applications, post-Olympics, for a whitewater course

The Olympic spend will gift Brisbane two big-ticket legacies – the Gabba stadium rebuild and the aquatic Arena on Roma Street. Around two billion dollars more will be spent on indoor stadia and venue upgrades beyond the inner city.

All qualify as legacy investments of public money, easily multi-purposed across a wide range of popular sports and community activities long after the Games. The whitewater course proposed for Birkdale is the stand-out exception.

A canoe slalom course is purpose built for that sport alone.⁵ It’s a highly artificial construct – a few hundred downhill metres of reinforced concrete forming a water channel steep enough to mimic the tumbling descent of a wild river. The illusion is sustained by massive electric pumps. These force megalitres of water back uphill, fast enough to feed the roiling cataract which the paddlers must navigate.

Being purpose built, whitewater courses have a narrow range of post-Olympic utility – unless you’re a paddler. Their climate legacy is a problem too – the carbon footprint of acres of reinforced concrete⁶ and gigawatts of electricity demanded by the huge pumps.

These negatives cut in as soon as the Games leave town, and have already compromised the legacy, even the survival, of Olympic whitewater venues. After Athens (2004) and Beijing (2008) their canoe slalom venues were simply abandoned. Rio (2016) has only recently re-purposed the Deodora complex as a public pool.

And the venues that have stayed afloat, like Penrith, and London from 2012, don’t owe their survival to ‘elite or community sports’. The bills are primarily paid by the ‘thrills and spills’ of rubber rafts, packed with paying customers, careening down the cascades of pumped water.⁷ Supplementary income is gleaned from canoe sports, and side-hustles like flood rescue training, and the occasional film crew.

Of course, the Penrith facility is a boon to Australian canoeists, and our Olympic champion Jessica Fox owes much to its existence. But it’s a minority sport. It will never underwrite the towering costs of infrastructure and energy on which it depends. Penrith’s electricity bill for its huge water pumps is around $90,000 a month. That’s a lot of rubber raft customers at $100 a pop.

The costs and benefits to the community

The best predictor of the likely impact on Redland City’s council, ratepayers and business is the Penrith Whitewater Centre’s civic history over 23 years. In summary, it’s been a roller coaster ride of sporting highs, and financial lows.

The highs are led by Olympic gold medallist, Jessica Fox, the French-born daughter of elite European canoeists who migrated to Sydney prior to the 2000 Olympics and built Penrith’s reputation as a world centre of canoe sport.⁸ The spin-off for paddling, and local business, is Penrith’s hosting of national canoe championships, and most international meets in the southern hemisphere. That global status attracts numerous elite paddlers from Europe and the U.S. who arrive in the city every year to avoid the northern winter.

Redland City is too late to the party to expect a share in these benefits. In a puzzling about-face the Council has now re-branded its white-water proposal as the Redlands Resilience Training Centre. Upskilling emergency workers in swift water rescue is highly desirable, and Penrith already does all the swift water training that’s asked of it. But it’s not a decisive revenue raiser.

Local canoeists would enjoy a world class facility at Birkdale. But, as the Penrith management has found, they will not pay a premium to use a publicly-funded venue. And neither they should.

The lows are financial – the annual losses the Penrith complex has posted for most of its existence, millions of dollars, underwritten by the Penrith City Council. Well before the Covid disruption, the PCC’s 2018-19 budget reported a revenue fall of nearly $400,000 from the whitewater course.⁹ Not enough rafts packed with local thrill-seekers – whitewater’s core business.

Since then, exponential hikes in electricity costs, Covid restrictions, and flood recovery, have made Penrith’s existence even more precarious. The takeover by the NSW government is clearly a strategic intervention to guarantee the venue’s future.

Would Penrith’s setbacks be replicated by a new build in Redland City? A recurrent theme of new whitewater facilities, world-wide, is initial struggle, dashed revenue forecasts, high-cost bailouts, and management upheaval. Nothing about the Redland City whitewater proposal suggests a better trajectory. On the contrary, the viability of whitewater courses is greatly dependent on population density.

The most successful Olympic whitewater venue to date is the Lee Valley course built for London 2012.¹⁰ It’s now run by the UK’s largest operator of leisure/sports facilities. Lee Valley is on the edge of Greater London, with a population over 9 million. Greater Sydney, an area of about the same size, has 5.3 million. A whitewater venue in Redland City would depend primarily on Greater Brisbane for its patronage – a population of around 2.6 million – less than half Penrith’s principal catchment.

The Redland City Council has not released a business case for its whitewater proposal. We cannot know how, or even if, it plans to counter the unpredictable liabilities that so often afflict new courses. Bigger councils than Redland City, world wide, have been rocked by cost overruns, pump failures, and management woes, creating early losses in the millions.¹¹

There’s also an apparent absence of local goodwill towards the whitewater proposal. The Council has held promotional events on the Birkdale site and asked residents to rank compatible activities, including the whitewater course, that might co-exist across the large precinct. The replies, from 1,680 respondents, favoured nature trails (78%) and a variety of conservation, heritage and educational activities. Support for the whitewater course was limited to 149 respondents, less than 9% of those surveyed.¹²

I began writing this with an open mind. I finished without finding a single compelling reason why $100 million of public money should be spent replicating the world-class canoe slalom course, ready and waiting, in NSW. I hope, for the sake of my own city, and its ratepayers, the Penrith Whitewater Centre will soon be declared the canoe slalom venue for the 2032 Olympic Games.

Peter Wear

Endnotes

1. The projected cost of the latest United States’ Olympic whitewater course, at Montgomery Alabama, is A$113 million (US$75 million) https://www.enr.com/articles/55746-montgomery-ala-whitewater-project-builds-more-than-rapids

2. 82 slalom canoeists will compete at the 2024 Paris Olympics. There will be 340 shooters, 288 wrestlers, 212 fencers, 212 table tennis players, 128 archers, 120 weightlifters, 88 skateboarders, and 32 breakdancers. https://olympics.com/en/sports/

4. IOC Feasibility Assesment – Brisbane 2032 https://stillmedab.olympic.org/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/News/2021/02/IOC-Feasibility-Assessment-Brisbane.pdf

5. Canoe slalom champions 2022 at the Penrith Whitewater Centre, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZgQtDhZJR1U

6. https://www.climatemediacentre.org.au/solid-solutions-sneaky-polluter/

7. Whitewater rafting at Lee Valley Olympic venue near London.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pgdus_8JTOk

8. Interview with Jessica Fox, Australia’s champion paddler, on her rise to world class from her childhood at Penrith. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S92Gcdpa36c

9. Penrith Annual Whitewater Report in Penrith City Council Policy Review agenda.P.43

http://bizsearch.penrithcity.nsw.gov.au/PCCBPS/Open/2019/12/PRC_09122019_AGN_AT.PDF

10. Lee Valley Olympic Whitewater course from London 2012.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lee_Valley_White_Water_Centre

11. Oklahoma Olympic whitewater course receives shortfall millions from city council

https://www.oklahoman.com/story/news/columns/2018/06/29/advisory-committee-oks-reimbursement-for-whitewater-park-costs/60516130007/ https://www.oklahoman.com/story/news/columns/2019/09/24/river-seeks-15-million-from-council/60433081007/

12. https://redlands2030.net/birkdale-community-precinct-vision-ignores-community-feedback/

Redlands2030 – 21 May 2023

Please note: Offensive or off-topic comments will be deleted. If offended by any published comment please email thereporter@redlands2030.net

2 Comments

Toondah Harbour Marine Park must be protected from wealthy real estate developers having control of a coastal wetland site that belongs to the people, all of the people, for all time. Plan to build high rise buildings with 3,600 apartments would destroy not only the marine park and protected mud flats migratory birds like the Eastern Curlew fly to from as far away as Siberia…but quality of life for Redlanders who value the natural surrounds that includes our endangered koalas. Resulting traffic congestion from motor vehicles would add to pollution related illnesses as local roads today, here in Capalaba, Finucane Rd. having seen too many deaths from crashes ,peak hour traffic begins around 2:00 p.m. Public transport is poor in Redlands where most of us are dependent on personal transport. Give nature a chance..save our Bay.

Well said Peter Wear an excellent presentation and explanation of the case against the White Water Facility planned by Redland City Council for the Birkdale Community Precinct. The local Community does not want it. Let’s hope the IOC intervenes and makes Penrith Whitewater Centre the dedicated venue for the 2032 Olympics.