Since the management of the environment is, by definition, a social and political process, it stands to reason that responses to environmental problems must focus at least in part on questions of human behaviour.

Environmental managers need to know how their interventions alter the motivations and thus the behaviour of people causing environmental problems. Yet social processes are often neglected by scientists and in real-world environmental decision-making. This neglect compromises the effectiveness and efficiency of the global investment in environmental interventions by governments, businesses and individuals.

Key messages:

- Spatial conservation planning can be improved by incorporating multiple objectives, multiple actors and multiple uncertainties.

- Incorporating human and social dimensions into the evaluation of environmental policy options increases the robustness of policy decisions.

- Engagement with psychologists and social scientists can improve our ability to anticipate responses to policies, including feedback loops and perverse outcomes.

- We are only just getting started in applying socioecological thinking to environmental decision making. Many innovations and new opportunities are emerging as new disciplines like behavioural economics are applied.

The challenges of holistically managing social-ecological systems are typically complex, dynamic and multifaceted. Therefore, conceptual and quantitative models are important for understanding and characterising socio-ecological systems, and for making predictions about the outcomes of management. The Socio-Ecological Analysis and Modelling Theme of CEED builds on techniques from a range of disciplines to analyse, model and integrate knowledge about socioeconomic and ecological processes to improve environmental decision-making. Here we present some of the highlights of this research theme and describe the evolution in thinking and method development that has occurred over the seven years of the Centre’s life.

Considering multiple objectives, actors and uncertainties in planning

Spatial conservation planning can be improved by considering multiple objectives, multiple actors and multiple uncertainties. In so doing, conservation planning is simply aligning with real world practice. Conservation planners need tools that match the world they are trying to plan for. This includes real-world complexities, constraints, uncertainties and political realities. Many conservation initiatives do not fit the single-actor, single-action model underpinning most conservation planning tools. This is particularly a problem in complex planning environments, such as the urban-fringe, consider the planning work done in Bekessy et al (2) or highly modified agricultural landscapes, where high biodiversity values must compete with multiple social and economic interests. Over the lifetime of CEED, Centre researchers have addressed important gaps between conservation theory and real-world practice by considering multiple actors, multiple conservation actions and multiple uncertainties. Some examples of this work include our research on collaboration and the incorporation of social values into conservation planning.

Optimising resource allocation through collaboration to achieve conservation objectives

In a setting where multiple actors have similar conservation objectives, strategic collaboration may optimise their resources to achieve conservation objectives, thus freeing up resources for additional work. Gordon et al (4) demonstrate that the cost savings from collaboration could vary significantly in different situations, ranging from a given actor making almost no savings through to saving almost 40% of the cost of achieving their objectives in isolation. The largest potential gains from collaboration occur when the conservation objectives of the two actors involved non-overlapping sets of species.

Integrating social values into spatial conservation planning

Understanding how society perceives and values different areas of the landscape is important for effective land-use planning.

Socially-acceptable conservation planning

Understanding how society perceives and values different areas of the landscape is important for effective land-use planning. Indeed, making use of social values is arguably one of the most important challenges in modern conservation planning, yet their potential remains poorly exploited. Previous research suggests the inclusion of social values can reduce conflicts between stakeholders and enable a more efficient implementation of conservation actions. However, the potential trade-offs related to incorporating social values into spatial conservation planning are not well understood.

Amy Whitehead and colleagues collected spatial data on social values by conducting a Public Participation GIS (Geographical Information System) survey in the Lower Hunter Valley in eastern New South Wales (Whitehead et al, 2014). Local residents were asked to map areas perceived to be important for their natural or potential development values. Randomly selected landowners were given a map of the region and a set of sticker dots that corresponded to different social values, including biodiversity, natural significance and intrinsic value types (social values for biodiversity). Another set of stickers corresponded to areas believed to be appropriate for different types of future development (social values for development). Participants were asked to place stickers on areas of the map they associated with each of the social values for biodiversity and development. The responses were then digitised and used to create density maps for each social value in the region.

In addition to this data on social values, the researchers used biological data to represent areas important for conservation. Seven fauna species considered to be vulnerable to land clearance were selected to represent the biological values in the Lower Hunter Valley. These species were mapped onto the landscape using species distribution models, derived from occurrence data.

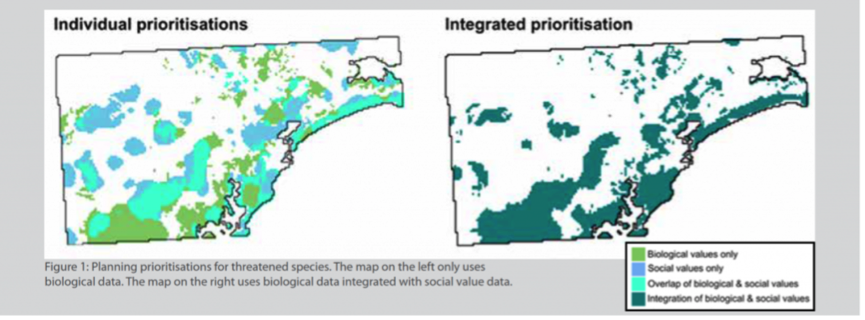

Not surprisingly, the best option for conserving the seven threatened species included in the model was the distributions obtained when the prioritisation only considered biological data (Figure 1). Interestingly, however, a similar proportion of each species’ current distribution was captured when biological and social values for biodiversity were integrated and prioritised together, although the spatial location of some conservation areas changed. Even when the areas perceived to be most important for development were forced out and the remaining sites were prioritised for both biological and social values for biodiversity, Zonation (the planning software used) still managed to find a solution that gave reasonable protection to the seven fauna species. This is good news for planners as it demonstrates spatial flexibility in the way conservation targets may be met in the Lower Hunter Valley.

Indeed, making use of social values is arguably one of the most important challenges in modern conservation planning, yet their potential remains poorly exploited. Previous research suggests the inclusion of social values can reduce conflicts between stakeholders and enable a more efficient implementation of conservation actions. However, the potential trade-offs related to incorporating social values into spatial conservation planning are not well understood. These gaps in knowledge led Amy Whitehead and colleagues to investigate methods for integrating social values into spatial conservation planning.

Incorporating human and social dimensions into policy evaluation

Incorporating human and social dimensions into the evaluation of environmental policy options can improve the robustness of policy decisions.

Decision science provides the necessary tools for rational decision making under uncertainty and complexity (Raiffa, 1968). The discipline has evolved rapidly in recent years with Australian scientists leading theoretical developments and applications in environmental management and biodiversity conservation. This is reflected by an increasingly significant role of decision science in conservation decisions in Australia. Sophisticated ecological and economic models are now available to help inform environmental decision making in the key areas of climate change adaptation (eg, Wintle et al, 2011), efficient monitoring strategies (eg, Wintle et al, 2010) and managing threats to species persistence (Nicholson et al, 2006).

While the sophistication of environmental decision models has improved, incorporating social science is still in its infancy (Milner-Gulland, 2012). This is an important limitation as understanding human demography, behaviour and socioeconomics is critical to understanding and managing ecological patterns and processes (Liu 2001).

More specifically, improving the effectiveness of complex policy instruments such as biodiversity markets requires a better understanding of human responses to incentives and disincentives because they determine the success or failure of such policies (1). By failing to consider social science in environmental decision making we are at risk of choosing strategies that are unlikely to work.

Biodiversity offsets are a point in case. These are an increasingly popular policy mechanism whereby developers ‘offset’ a development by enhancing natural values elsewhere. But a failure to consider social values in the policy formulation makes perverse outcomes much more likely (5).

Psychological insights and social values

Engagement with psychologists and social scientists can improve our ability to anticipate responses to policies, including positive or negative feedback loops and perverse outcomes. Consider these examples.

Strategic framing of biodiversity in neoliberal terms may have unintended impacts on how people perceive and engage in biodiversity conservation. Consider the increasing use of utilitarian values to define nature. For example, there has been a dramatic increase in the use of the term ‘ecosystem services’ which is framed as the value of the benefits provided by nature, something that can have monetary values attached to it.

Kusmanoff et al (6) analysed the language being used by environmental agencies and found that there has been a decrease in the use of the term ‘biodiversity’ and an increase in the use of economic language, including regular use of ‘ecosystem services’ concepts. In contrast, over the same time period, ‘biodiversity’ has increased in use within scientific literature. What does this mean for biodiversity conservation?

While this may reflect a strategic response by these agencies to better engage with both the general public and decision makers within what is an increasingly dominant neoliberal paradigm, we argue it may also have unintended (possibly adverse) impacts on how people think about and engage with biodiversity conservation. There is concern that consistent framing of biodiversity in economic terms (such as ecosystem services) will promote the value of biodiversity as a resource over its intrinsic value

Social values and psychological insights can also help in designing more effective environmental policy such as efforts to get more landowners to participate in biodiverse carbon plantings. Torabi et al (2016) sought to determine what drives landholders’ participation in biodiverse carbon plantings? They found that the rate of landholder participation depends on many social and environmental drivers. The amount of management required and the landholder’s value of biodiversity was in many cases more influential than financial incentives.

Values other than dollars was also important in understanding what make for a successful stewardship program over longer time frames (Selinske et al, 2016) and in maximising engagement with landholders engaged in private land conservation (6).

The way ahead for socio-ecological thinking

In terms of socio-ecological thinking, we’re only just getting started. Over the seven years of CEED, the interdisciplinarity, sophistication and robustness of our approaches to embedding social complexity into decision science has grown substantially. We’ve moved from simple economic models of human responses to environmental interventions to much more nuanced understanding of how to represent values, predict how people may respond individually or collaboratively, and understand how to design messages and programs that are more likely to achieve desired behaviour changes.

Yet, we are really only getting started! This research space presents many exciting challenges, both theoretical and practical, and the demand from policy makers for socioecological thinking is only growing. A key theoretical challenge is how do we move from the rational optimizer to behavioural economics and beyond? How much social complexity versus ecological complexity should we include in our models?

We have identified judicious opportunities to advance research in socio-ecological analysis and modelling. This has been largely due to recent innovations in social research, especially in the area of behaviour change. For example, the field of behavioural economics (a partnership between economics and psychology) has significantly influenced the way that governments attempt to influence behaviour in many sectors, including health and taxation. Its application to the environment, however, has so far been minimal. We can also draw on the innovative idea of ‘experimentalism’ from sociology, which adds value to the established approach of adaptive management, and the research field of ‘political communication’ from political science, which is concerned with production, dissemination, procession and effects of information within a political context.

These research fields have significant untapped potential to contribute to improved thinking and decision making about environmental management and policy. Importantly the new insights generated will allow for the design of environmental policies to achieve desired behavioural changes more efficiently and reliably, and in ways that do not undermine existing pro-environmental behaviours and motivations.

Environmental decision science has come a long way in recent years in helping decision makers navigate an increasingly complex world. And yet the social and psychological dimensions of this complexity are only now being understood and acknowledged. The big challenge is to effectively incorporate these new learnings into the way we make decisions.

References:

- Bekessy SA & B Cooke (2011). Social and cultural drivers behind the success of Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES), In: Payment for Ecosystem Services and Food Security. Ottaviani, D & N El-Hage Scialabba (eds). Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome. pp. 141-155. http://www.fao.org/rio20/special-features/payments-for-environmentalservices/en/

- Bekessy SA, M White, A Gordon, A Moilanen, MA McCarthy & BA Wintle (2012). Transparent planning for biodiversity and development in the urban fringe. Landscape and Urban Planning 108: 140-149. For a discussion on this paper see Decision Point #68

- Bekessy SA, MC Runge, AM Kusmanoff, DA Keith & BA Wintle (2018). Ask not what nature can do for you: A critique of ecosystem services as a communication strategy. Biological Conservation 224: 71-74.

- Gordon A, WT Langford, L Bastin, AM Lachner & SA Bekessy (2013). Simulating the value of collaboration in multi-actor conservation planning. Ecological Modelling 249: 19-25. For a discussion on this paper see Decision Point #73

- Gordon A, JW Bull, C Wilcox & M Maron (2015). Perverse incentives risk undermining biodiversity offset policies. Journal of Applied Ecology 52: 532–537 doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12398 For a discussion on this paper see Decision Point #91

- Kusmanoff AM, MJ Hardy, F Fidler, G Maffey, C Raymond, MS Reed, JA Fitzsimons & SA Bekessy (2016). Framing the private land conservation conversation: Strategic framing of the benefits of conservation participation could increase landholder engagement. Environmental Science & Policy 61: 124-128.

This article was written by Professor Sarah Bekessy RMIT University, where she has been teaching in sustainability and urban planning since 2004. The article is re-published by Redlands2030 the permission of Professor Bekessy and the CEED publishers of Decision Point Online.

Decision Point is a magazine on conservation decision science, which ran from February 2008 – December 2018 and it was published by CEED, the Centre fo Excellence for Environmental Decisions . Decision Point was the free bi-monthly magazine of the Centre of Excellence for Environmental Decisions (CEED), which was funded by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council Centres of Excellence funding scheme from 1 July 2011 until 31 May 2018. In December 2018 the last edition was published.

Redlands2030 – 7 August 2019

Please note: Offensive or off-topic comments will be deleted. If offended by any published comment please email thereporter@redlands2030.net

11 Comments

Comment on complexities of integrated planning and development decision making

The matters raised in the comment have merit.

Yes planning and development decisions, if they are to be made in the public interest, are complicated and involve consideration of the interplay of social, ecological and economic issues, especially the two former. However, no one has said that this task was to be easy.

Regrettably it would appear that many planners either do not have access to relevant locally available information and community values/interests or they do not see the need to seek this when planning scheme and development decisions are involved. It would appear that the preferred solution to complexity is to ignore information outside the planner’s area of expertise (possibly because of legal constraints, short times involved and agency interests). This is a shame when there are others both capable and willing to address any information deficiency so as to enhance the achieving of appropriate shared outcomes.

I always thought that this integration of information and minimisation of conflict was best addressed during the plan preparation phase when land uses and when performance outcomes are to be reflected in relevant codes. Regrettably, I am only too familiar with plans being prepared with codes, which purport to, but do not, address plan intended outcomes are put in place but do not meet the public’s expectations and interests. This particularly applies when ecological and social values are involved. How come we now have codes for aged care and retirement-living that do not appear to take into consideration health-related matters?

It is a tragedy that there continues to be a major gulf between the intent of plans and how development decisions are made – allegedly achieve that intent. I thought that the primary purpose of planning phase was to address the following matters that cannot be adequately addressed solely at the development approval phase:

• Maximise certainty while recognising the need for an appropriate level of flexibility in a complex “environment”.

• Avoid predictable inappropriate decisions being made. Is this the reason for ignoring available knowledge, as this might complicate someone’s preferred decision being made?

• Addressing cumulative impacts of development decisions.

I cease to be amazed that when professional advice is offered to assist decisions to be made in the public interest and which recognise the legitimate community concerns that this advice is frequently ignored without explanation. No wonder conspiracy theories are all the rage. I must have misheard as I thought planners and government were promoting public engagement!

Maybe input by informed members of the public is needed rather than planning workshops that appear to be “marketing exercises”.

As an academic, permit me to say what is happening right now in the Redlands. It is too important to be side tracked by academic arguments of people who stand on their own soap boxes and debate abstract ideas, some of which are totally devoid of any association with what is actually happening. Each of these writers, including Sarah, have made some good points but we can see they are at odds with each other. One writer talks about applause, referring to the quality of planning and decision making. I will be blatantly clear. There is no reason for any applause. The only people who will be applauding are the Mayor of RCC and a couple of her ardent supporters, who to this point have seen R2030 as a threat to their goals. Now we have moved away from the flawed thinking around the Walker Proposal and other PDA’s in the Redlands, which threaten our environment, our wildlife and the very lifestyles we enjoy. Sarah summarises:

“The challenges of holistically managing social-ecological systems are typically complex, dynamic and multifaceted. ”

That may be the case in an idealistic world but here in our world we are faced with a Mayor and a number of councillors, who give developers what they want because more medium to high density housing means more money in rates for the Council. Let’s just look at one proposed development, that of 3,600 units for Toondah Harbour. If each unit was to pay only $2,000 per annum in rates to RCC, which is an under-estimate, the annual rate return to the Council would be over $7,000,000 per year. That is a tidy annual sum from one development. Who will then pay for all the infrastructure? Why the rate payers of the Redlands of course. While you academics discuss the pros and cons of various planning and political strategies time moves on and so does the unhealthy relationship between developers and your elected officials. Perhaps your time would be better spent writing to the Federal Environment Minister, as I have just done, or to the CCC.

As a practical man, I’m delighted to hear that coming from an academic, Dennis.

Nowadays, academics don’t usually want to solve a problem, because their funding would evaporate, and it’s also important that the solution aligns with the funding source’s agenda, or criteria.

Your assessment of the situation is basically true, but there’s an additional element that hasn’t been mentioned. If we accept the idea that Council will make a fortune in rates from developments, because it’s true, the counterpoint is that everyone else’s rates should logically reduce as the revenue stream broadens and deepens. Then, one step further, it’s obvious that destructive social issues will manifest in “low cost” densely populated communities, which then provides justification for expanding all public services, whether they’re state or federally funded. Considered holistically, these unwanted developments are only the first element of the Hegelian Dialectic, Problem – Reaction – Solution. These developments create a problem for Govt to solve, who then manage the reaction to the problem through the media, and finally offer the previously prepared solution that no-one in their right mind would want.

I only have one criticism, if you can call it that. Your last comment about writing to the minister or the CCC won’t work either. They’re in basically the same boat as academics, reliant on funding from Govt, so the last thing they’d want to do is bite the hand that feeds them. Granted, councils are getting a thrashing in the media lately, but that’s more likely part of a bigger agenda to “force” councils to amalgamate, which will give them even more power. What could possible go wrong?

Thanks Sarah with concepts from a different school of Social Planning. The early sentence in italics is pertinent to greater Brisbane periurban fringe which once had 2 Greenbelts IE inside BCC and the other containing the Koala Coast, parts of Logan , parts of the FGK Corridor and Ipswich and parts of the D’Aguilar Range and Pine Rivers and a few (IUBs)Inter Urban Breaks . These have been largely eliminated by Urban Footprint and Planning Acts 2016-, without Regional Environment Assessment by DTMR ,DSDMIP and The points raised by Geof Edwards and Dave reflect the unsustainable deterioration of many aspects of Town and Regional Planning. It appears we have lost Social Planning in ; formal positions , public policy and legislation in Queensland . This vacuum is reflected in poor planning outcomes,leading to homelessness and parlous state of overworked voluntary,statutory and other social services .

The Key Messages have some other subsets (some mentioned) including socio economics, ecosystem services (SEQRPlan 2009 and Healthy Land and Water), Community Learnings(see Harbinger Report 2011), Social Contracts, Input Output reports for jobs and Social Media. The attempts to place SIA in the EIA should be mandatory. However Mandy Elliott in Environmental Impact Assessment in Australia at 9.18 “Finally What Hasn’t Been Said” states “EIA has a tendency to be used as a vehicle for assisting development to occur,and may not give adequate attention to alternatives.” “…EIAs are also based on value judgements and are political decisions. Indeed EIA is both a technical and political process.” This is why Needs Assessments, Social Surveys and Independent Reports (GBRMP) are needed for Toondah Harbour .

Only an academic could think they know better than practical people, and how our thinking needs to change, not theirs. For those not accustomed to reading academic papers, allow me to translate some of the points made above.

“We have identified judicious opportunities to advance research in socio-ecological analysis and modelling. This has been largely due to recent innovations in social research, especially in the area of behaviour change.” In plain language, they’ve found some government money is available in working out how to control human behaviour to suit their agenda.

“A key theoretical challenge is how do we move from the rational optimizer to behavioural economics and beyond? ” This asks how can we change decision making from optimizing rational choices to making people respond to economic pressures like Pavlov’s dog to a whistle.

It’s alright though, these people are professors, and that makes them qualified to accept huge piles of our tax dollars to tell us something we either already knew, or didn’t want to know. In this case, Sarah will be working out how bureaucrats and politicians can tell us things we don’t want in such a way that most of us are cheering, rather than booing. The whole idea is making us like what they want to give us, rather than giving us what we want, and making us pay.

That’s a rather jaundiced view, Peter, and an incorrect portrayal of Sarah’s theme. Sarah is making the point that humans are motivated by much more than money. The project is an attempt to ascertain what “practical people” really think and to devise a formula or method by which the views of “practical people” can be integrated into decision-making about the environment. There is no suggestion of “controlling” human behaviour, rather the theme is to understand human behaviour.

“Rational optimizer” does not mean “a rational practical person”. It is a jargon term for the notional unit at the centre of economic modelling, which is an entirely self-interested individual. No such person exists. We are all subject to a range of motivations including selfish, family-centred and civic-minded motives.

I would have thought that attempts by our academic community to improve the quality of decision-making about the environment should be applauded.

The gap between ‘real planning” and statutory land use planning (in the form of planning schemes) is getting wider and wider. The Statutory planners have no regard to a modelled or repeatable process … it all just a whim. The conclusion is clearly the planning used for planning schemes is planning in name only and is a debased form of planning that is really all about development and development approvals.