Will “Australia’s best planning system” mean no more protests against development applications?

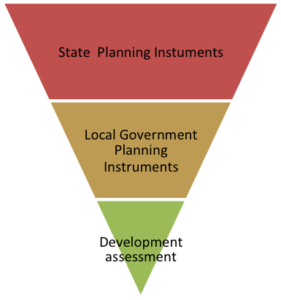

The Planning Act 2016 establishes a hierarchy of planning instruments to articulate local and statewide land use policy and sets the foundation for development.

- State planning instruments are produced by the state and local governments must have regard to when developing their local plans

- Local planning instruments are “owned” by local governments and collectively guide planning and development across the state

- Statutory instruments mandate the how, to ensure operators of the system are consistent and the community has certainty.”

The State Government describes plan making as providing “the foundation for development to occur across the state”.

Development has a specific meaning and ultimately a local government planning scheme can only legally address and enforce matters relating to development.

While forward planning instruments, such as Strategic Frameworks, will consider broader community, economic and environmental policy issues in their preparation stages, these particular planning instruments often do not operate as the preeminent planning instrument for most of these matters (i.e. policy implementation is achieved through a number of mechanisms of which local government planning schemes are just one mechanism). At the end of the day the courts in any appeal process will often only look at development from a strict legal interpretation as to how it complies with the land use requirements. It may consider matters as to what was the policy intention, but it won’t re-invent the policy intent as that remains the prerogative of the law makers.

How the new Act will work?

The new Act continues the previous system of “cascading” or “top down” plans that eventually integrate into the local government planning schemes. These schemes are the “front end” for accepting, processing and determining development applications. This is the process that generates most community angst about neighbourhood development, change and local amenity.

The State uses two types of planning instruments that must be taken into account by a council when preparing its local planning scheme. While there is always some small level of negotiation regarding what is a “State Interest“, there are nevertheless mandated requirements that the council has little control over. The two State Planning Instruments are:

- State Planning Policies: these are intended to apply across the State and tend to address statewide issues (e.g. protection of good quality agricultural land).

- Regional Plans: these provide the opportunity for more refined analysis of more specific issues that exist within a given locality on a scale beyond the local government level. In the past regional plans included issues that extend beyond the narrow remit of land use planning such as natural resource management planning, water planning, transport planning regional landscape planning. Regional plans are concerned with planned outcomes not just development approval processes.

Taking into account any State requirements, the local council is responsible for developing its own planning scheme. As in the past, it will be developed in consultation with the community. The Department makes much of new, non-mandated, community consultation tools that it intends to roll out, but as yet are undeveloped.

The third element of plan making, statutory instruments, provide a wide collection of process or how to guides for making plans. These are more directed at the practitioner, but may be of interest to people in the community who are trying to understand proper process.

Implications for making planning schemes

1. Primacy of plan making

The key implication is that plan making is still paramount and once the strategic directions or policies are set – then (in theory) lower level planning instruments will follow through to implementation. Any mandated State or Regional policies will be integrated at the local government level, which in turn will be supported through the wording and application of lower order development assessment instruments (e.g. strategic framework, zone and use codes etc). Local government planning policy (consistent with State policy) will be drafted and applied in the same way.

For communities it follows that if you lose the battle at this higher order level, then it will be unlikely that you can stop approval of an application for a development in your neighbourhood if it’s in the right zone and it meets all the relevant land use requirements.

2. Operationalisation

Like previous legislation the new Planning Act is very process driven. This includes how these plans are prepared and amended. Very little is said about what plans must achieved, other than compliance with the purpose of the Act which is to:

…establish an efficient, effective, transparent, integrated, coordinated, and accountable system of land use planning (planning), development assessment and related matters that facilitates the achievement of ecological sustainability.

Ecological sustainability (ES) is further defined in the Act [s. 3(2)] and is the balance between a range of considerations, not all environmental. It is a fair assumption that the balance point will differ according to any State mandated requirements and local facts and circumstance that the local government considers most important. The lack of any objective performance measures, whilst allowing for flexibility, will mean that the Act is itself silent (other than process) on what this ecological sustainability will look like in each local government area.

Thus the way that both State and Local Governments operationalise their respective policies and plans will have a large bearing on the intended outcomes. For example:

• One local government may decide to put more emphasis on economic development to the detriment of environmental outcomes, or visa versa. Both are valid approaches and will represent the balance point adopted by that particular local government at that point in time or

• The State Government may take a different approach with its Regional Plans and use them to be more specific in the intended outcomes, rather than the current motherhood type policy statements.

3. Meaningful public consultation is critical

For many (most?) people and communities, understanding the possibilities and complexities of what can or can’t be developed in any given area through a planning scheme is so complex that prevents meaningful engagement. Public consultation is something that most Councils don’t do well. When Councils consult there tends to be a focus on what you can or can’t do on an individual property. Rarely do councils engage in meaningful bigger picture questions like:

• this is what is proposed for your area;

• these are the reasons why;

• this is what we considered;

• this is why we chose this particular strategy over the alternatives;

• this is how it will be implemented.

These discussions WILL generate competing views, but this is necessary if councils truly want to engage their community. The community rarely speak as one voice and so conflicting strategic directions can never be fully resolved. Likewise, governments are often trying to achieve multiple outcomes, not all of which operate in harmony with each other and choices about primacy have to be made.

Nevertheless, these matters should be discussed in an open and transparent manner so the general public has a chance to understand the context and reasoning for the arriving at the final “balance“.

The new Act does not compel nor restrict the contents of any consultation (e.g. it can be simple or complex). The new Act does allow for a longer consultation timeframes. However, timeframes are academic if the way consultation is undertaken is not engaging or understandable for the person on the street.

Some people believe that consultation would be more fruitful and meaningful if undertaken at a local level. The Regional Plan and Strategic Framework can both provide the bigger picture, but a local area plan can provide the spatial scale in which people can readily recognise, comprehend and provide useful ideas or suggestions. Nothing in the new Act either compels or restricts such mechanisms or consultation, but it does have a resource implication for Council.

Taking a wider perspective, a Community Plan is often a better holistic planning instrument for setting the strategic directions for any given community. It allows the freedom to consider a wider range of issues outside the narrower development assessment parameters set by the new Act. The relevant aspects of the Community Plan can then be fed into the drafting of the local government planning scheme; and other aspects are feed into other relevant plans, strategies and projects of Council, businesses and community.

Conclusion

The State Government says:

The new legislation will provide the foundation for Australia’s best planning system and put Queensland at the forefront of contemporary planning practice and prepare the way for a renewed focus on quality planning and development outcomes.

Measured against these words of self praise the new legislation is underwhelming.

Plan making will still be very much a process that then depends heavily on its operationalisation to give it its intended force and effect.

This operationalisation is never easy, as there are many conflicting viewpoints and directions that can be chosen. Ultimately it seems likely to boil down to choices and/or compromises needed to be made between these conflicting outcomes.

As such this aspect of strategic planning deserves much better attempts to explain these choices and decisions with communication through means that enable all members of the community to understand planning choices and implications.

What do you think?

What actions are needed to improve development planning in Queensland?

Redlands2030 – 21 September 2016

Notes:

- Certain words or concepts have been emphasised to highlight key points or concepts that are important to understand and recognise.

- The commentary in this post should not be relied upon in any legal argument.

Please note: Offensive or off-topic comments will be deleted. If offended by any published comment please email thereporter@redlands2030.net

One Comment

No matter how many ‘new’ words or concepts appear in this document, it seems to me to be more ‘same as’ with extra avenues for buck-passing of decisions that are in opposition to ratepayers’ wishes and still no obligation for ‘public consultation’ to be heeded. This document has been long in coming but short on real direction. I wonder how much the State Government paid to have this document researched, reviewed, printed, discussed and distributed? Whatever the amount, I believe it was completed wasted and gives us no more certainty than before.